The BFGs (Big, Friendly Gems): What are the largest diamonds ever found? | Rare Carat

I am a small woman. A mere 5 ft. As a child, unsurprisingly, I was smaller than that. Pocket size, in fact. So, to reassure me, my mother would tell me that precious things come in small packages, and I would go to bed comfortable in the knowledge that my diminutive stature only added to my charm. Then I got mixed up in the world of diamonds, and all that was turned on its head. Bigger the better, apparently. And I was mortified.

But then I got to thinking. I know some perfectly precious *big * people. And, in the same vein, a tiny red diamond is worth far more than a hunk of white stone. So, sorry mum. It's not size that earns you the precious predicate. It is scarcity. That ‘you're one of a kind’, ‘they broke the mould’, that ‘once in a blue moon' type.

And large diamonds are scarce. In that great, hefty expanse of spinning rock we stand upon, it appears that it is incredibly infrequent that these little buds of brilliance grow to full bloom. We have been yanking these beauties out of their volcanic hosts for over a hundred years, from the rivers and streams for over two thousand, and the fact that I can only name three single crystal stones that surpass the one thousand carat mark - that says something about just how scarce they are.

So as Not to Disappoint

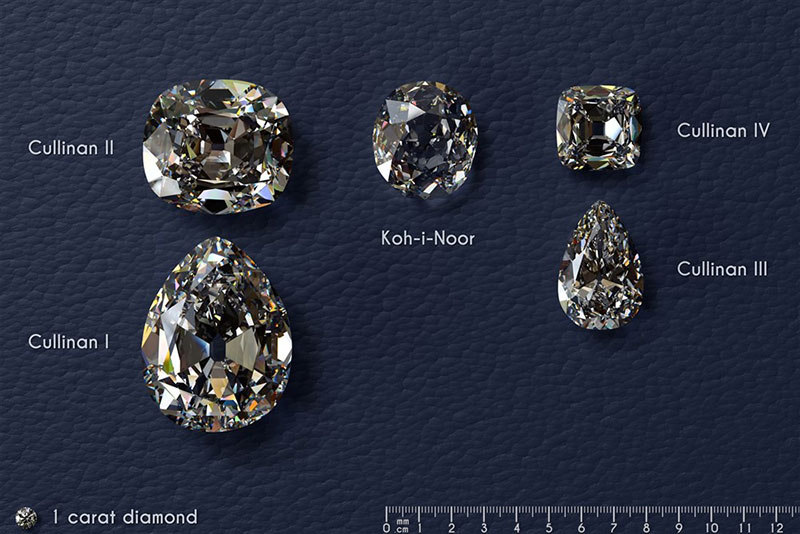

Now, before we go any further and I introduce you to these monster minerals, can I just manage your expectations. Diamonds, as are all gemstones, are measured in carats, a unit of weight equivalent to 0.2 grams. The majority of rough diamond production weighs in under ten carats, only considered large if they exceed that. And what is ten carats? Well, that’s the size of your everyday glass marble (am I showing my age? Kid’s still play with marbles, right?). Basically, large is still small, if you get me. Relative, say to the mineralogical sibling, Mexican selenite, which can grow up to 11 metres tall. (which is just showing off, really). In fact, when the most famous of the worlds largest diamonds, the Cullinan, was first displayed to the public in 1905, people were somewhat underwhelmed. Even though it weighed in at 3,106 carats, it's anticipant audience walked away muttering, “well that was just a fist sized lump that looked a little like wax”.

The Large Stone Line Up

Not meaning to be a snob about it, but let's cut it down to the true colossi amongst them, those diamonds that surpassed one thousand carat mark.

Sergio (or the 'oft forgotten'). Weight: 3,167cts. Found: 1895, Brazil.

This mighty diamond is frequently omitted from the honours list, as it doesn’t fall under the category of gem diamond. It is, instead, an aggregate of tiny diamond crystals fused together into one tough black lump, known as carbonado. This type of diamond is only found in Brazil and the Central African Republic, and more often than not, is used for industrial purposes. As was Sergio’s fate. Where, how and why carbonado forms remains somewhat of a mystery, with some theories expounding extra-terrestrial origin.

The Cullinan. Weight: 3,106cts. Found: 1905, South Africa

This still takes some beating, I have to say. The superintendent of the Cullinan Mine, Fred ‘Daddy’ Wells was convinced he was being taken for a ride by his colleagues when he first came across it, chipping it carefully out of the ground with his pen knife. (The knife was never used again, needless to say). This beast of a gem quality colourless stone was sold to the King of England and cut into nine major stones, the largest of the two now gracing the British Crown Jewels, and 96 minor brilliants. The best part is, it is likely that the Cullinan was only part of a much larger diamond. Oh, Mother Nature, the treasures you conceal.

Sewelo. Weight: 1,758 cts Found: 2019, Karowe Mine, Botswana

Meaning ‘rare find’ in Setswana, this one came gift wrapped. It is covered in a layer of black, carbonaceous material, so it does not look dissimilar to a lump of coal (Google it, you won't be disappointed). What is inside remains a mystery. It was sold to Louis Vuitton last year, and with the help of the tech whizz kids at diamond manufacturer, HB Antwerp, it is being cut into a number of gems. The quality of the Sewelo offspring, as yet, remains a mystery. Let’s hope it was money well spent, eh Louis? Fingers crossed.

Lesidi La Rona. Weight: 1,111 cts Found: 2015, Karowe Mine, Botswana

I’m rather fond of this one, mainly because I’m a sucker for a beautiful name. Christened by a resident of a small village in Botswana, the name means ‘our light’ in Tswana, because the diamond represents the pride and hope of the country. It was bought by Graff in 2019 for $53 million dollars and has now been cut into 67 stones, the largest being 302.37cts of emerald cut diamond. A cut that lends itself to anything that is whiter than white and cleaner than clean. Or D Flawless, if you want to get technical.

Notice the Trend?

The last two in the lineup come from the Karowe Mine in Botswana, and were unearthed in the last ten years. The Karowe, owned by Lucara Diamond Corporation, is becoming quite adept at pulling out some pretty large stones. This year alone they have already pulled up two 300 carat-plus gem quality pieces. Blessed by the Gods? Luck of the Irish? Not so much. A lot of it is down to a rather high spec recovery process. Old school methods of separating out the diamond and the rock it came up in can be a bit too bullish, resulting in large pieces being inadvertently broken up early on in the recovery process. Lucara started using a X-ray transmission sorting in 2015, a clever little method of scanning the rock using an x-ray camera, which spots all the denser stuff, including diamonds, regardless of their appearance, and saves the larger, big-money stones.

A Final and Profound Note

Clever tech aside, the largest diamonds Mother Nature has to offer still account for a teeny tiny fraction of total mined production. And there seems to be a fairly valid reason for that. They have further to travel.

Not so long ago, a select number of diamond nerds (collective noun: a sparkle?) noticed that most large diamonds were colourless, near flawless, and had no defined shape. Basically, they all looked a bit like lumps of broken glass. They nicknamed them ‘CLIPPIR’ diamonds, an acronym standing for Cullinan-like, Inclusion-poor, Pure, Irregular, and Resorbed. Digging a little deeper into the odd black spots they did find inside these magnificent monsters, they discovered that these crystals must have formed at extreme depths in the earth. I’m talking, way-way down, your spade ain’t gonna cut it, hotter than hot, deep. That’s up to about 660 kilometers into our precious earth. So, it turns out it's a factory-of-fabulous down there.

No wonder it only lets a few go.